Noble Falcon Pro TWS headphones: the review

Let’s get straight to the point: the Noble company managed to make some completely wireless headphones with very good sound. Like, phenomenally good sound. But are these Noble headphones themselves? This is actually a big question.

The Noble Falcon Pro (I’ll be calling them NFP further on) use a hybrid structure with a 6-mm titanium dynamic driver and an armature paired emitter manufactured by Knowles. The headphones are connected to the sound source via Bluetooth 5.2 and also support SBC, aptX and aptX Adaptive (only for Qualcomm SoC-based devices). One full power charge is enough for about 8–9 hours of continuous listening at 60–70% sound volume. The case is charged via either USB Type-C cable or wirelessly.

For security, there’s the IPX5 standard in place.

From the point of view of the functionality trend, the NFP aren’t that attractive, since these don’t feature active noise reduction or configurable sound transparency mode (it’s on or off, with no fun in between). They don’t even have sensors to detect whether they’re in or out of the ears. There’s touch control though (well, in fact, there isn’t… I’ll explain it below), there’s a native app with equalizer and some primitive capabilities to make you think you can change the headphones’ control scheme.

Usage experience

The shape of the NFP is uncharacteristic for TWS, but quite common for Noble headphones – they’re ergonomic and sport some long and rather thick sound ducts.

And it turns out that in reality such an approach results in an unexpectedly good sound insulation due to a very tight fit. Given this, it’s pretty much odd to realize that the headphones are actually comfortable in your ears, and you can for once be completely reassured they won’t parachute for parts unknown. Never.

The sound ducts of the headphones are protected by non-removable metal nets.

As an alternative to standard earpads, you can use both XELASTEC SednaEarfit or SpinFit or Symbio Eartips — these match the sound duct diameter just fine.

Well, going back to the touch control, you don’t really touch the NFP to control them. You tap them on any part of the enclosure. So you don’t necessarily need to target the backplate with your finger. You can even fillip on your ear — you’ll get a red ear and the next track on your playlist. Isn’t it convenient? Well, you really don’t need to aim at the touch pad, this is an absolute win. On the other hand, there are no gestures like long touch here, there’s one, two- and three-fold tapping. Tapping your finger on the earphone three times to increase the sound — and this is a regular setting — is a bit dubious pleasure, to say so. But this is still not the main thing about these headphones. They actually respond to taps, touches and shocks in all cases.

- You take off your t-shirt, its hem clings to your ear — the music stops.

- You pause your music, pull the headphones out of your ears and put them on the table — the music starts playing.

- You put the headphones in the case, they click into their magnetic slots — the music either turns off itself, or starts playing again for a second, until the headphones realize they’re home and are supposed to stay quiet in there.

- Or, for example, you take the headphones out of your ears to order coffee holding them in your hand, they knock against each other — aaand the music starts playing, then stops, then plays again and so on.

Dear manufacturer, here’s a good piece of advice for you: test your headphones before releasing them. Testing is your bro. I don’t know, let your QA staff use them for a day or two just like your future consumers. Didn’t you think about that? Pity,

I also have a couple of thoughts about the case. Well, not exactly about the case itself, but about its functioning logic. When the headphones are placed in the case, orange diodes on them light up indicating the charging status.

And if the case is charged less than is necessary to fully charge the headphones, then the following happens:

- The headphones begin to charge draining the what’s left in the case.

- The headphones quit detecting the case and think that they were taken out of the case.

- If your smartphone is somewhere nearby, they automatically connect to it, sometimes without you noticing it if, for example, you’re busy working.

- The headphones, being connected to the sound source, are slowly but steadily discharged to zero.

And voilà — you think there’s a couple of hours worth charge left for a pleasant evening, but no sir, this ain’t gonna happen: here are your discharged headphones and a dead case, thank you very much.

You may want to know WHYYYYY, and here’s the crappy truth: it’s because the manufacturer were too lazy to play around with the headphones to find out how the product they created would actually work in real life.

Although there’s something I feel obliged to praise the NFP for, and that’s for the connection stability. There are no stutters during playback, regardless of which pocket of your pants or bag your phone is in, whether it’s noisy around or not in the subway, gym, or wherever you may happen to go. During two months of use in various conditions, the NFP sound was interrupted only once, when, while tying my shoelaces, I accidentally clamped the phone in my breast pocket between the front of my thigh and my chest. That being said, in terms of connection stability the NFP unconditionally beat, for example, the Bowers & Wilkins PI7, Master & Dynamic MW08, RHA TrueControl, Sony WF-1000XM4 and Sennheiser Momentum True Wireless 2.

Native app

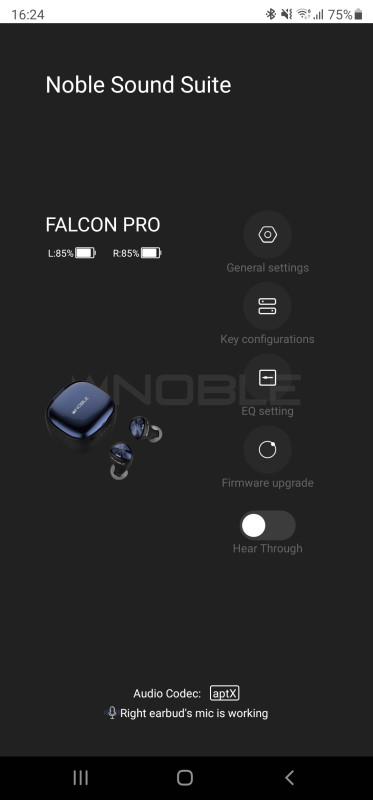

The proprietary app is called Noble Sound Suite (V2. 1).

I’m not going to describe in detail what’s already clear from the screenshots here. I’d only say that to have the app work with the NFP okay without giving you pain, without making you suffer, desperately cry and break the walls with your head, you need to update the headphones’ firmware to version 4.0. Do it, and you’ll find peace of mind.

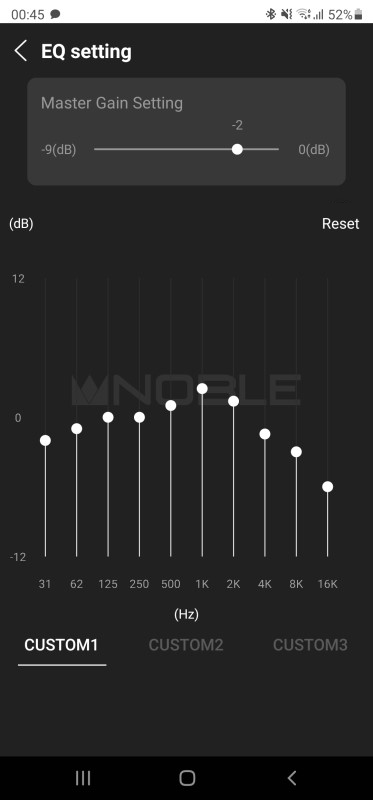

The main useful feature is sound equalization, and the currently active equalizer settings are stored in the headphones’ system itself.

It’s possible to save 3 presets for 10 bands in each + the gain value. Is it possible to somehow make a bad equalizer ? Yes. The Noble must know the special technique for this: the shift value for the frequency is displayed only when you touch the band with your finger, and the band itself doesn’t change values discreetely, but smoothly. The values themselves are discrete, even figures with +/-1…12 dB increments. That is, a fairly significant gap is available for each figure. Aren’t you the clever cookies, Noble? (No.)

Oh, by the way: you can’t change the equalizer profile without using the app.

You can immediately reconfigure the control, but only for two or three taps options, you also can update the firmware, turn on the sound transparency mode or choose the display language. English to Japanese, so Japanese users are safe on this side.

With such limited functionality, the app is also unstable even after updating the firmware of the headphones. The app can stop detecting the headphones all of a sudden, both when connected to a sound source based on Qualcomm SoC, Exynos or Kirin. It can reset the equalizer preset that the user has tuned through pain — just like that, when it feels like it.

App updates are rarely released, too, and the 2-star rating in Google Play kind of reflects the reality.

Listening experience

For the listening test, the headphones were connected to a Samsung Galaxy Note 20 Ultra smartphone (Exynos SoC) and a Hiby R5 player (Qualcomm SoC); the aptX codec was also used.

Despite all the control flaws and the frankly low quality of the software portion, the Noble Falcon Pro make you totally in love with them. Insert them into your ears, turn on the music… And you’re gone. You wouldn’t even think that some TWS headphones can sound almost the same as a wired hybrid model using similar tuning from the same cost range.

Well, I didn’t think they could, and yet here I am writing good things about this headphones type.

By default, e.g., without equalization, the NFP feature some heavyish, but at the same time kind of dry and sparkling V-shaped delivery, and the sub-bass is additionally emphasized, as well as a section around 12.5 kHz that’s far beyond measure. That being said, by default, the headphones sound very dynamic, assertive, and with a distinguishable unpleasant rasp.

Of course, I wasn’t satisfied with such a delivery, so I tried to experiment and came to the equalizer setting on the above picture. Unfortunately, there’s no slider at the 12.5 kHz point in the equalizer, but this peak can be somewhat smoothed through the sliders at 8 and 16 kHz. I aimed to achieve a more even delivery, so the mid-frequency range was also raised, and the sub-bass was adjusted.

It’s worth noting that, quite in the spirit of the general software clumsiness, when the equalizer is active, at the very beginning of music playback, you literally hear the non-equalized source sound for some third of a second, and only then your settings are applied to it.

Sound stage, dynamics, detailing

The sound stage is pretty wide for in-ear headphones in general, and quite unusually wide for wireless ones. Not least because even with the equalization offered, the headphones make ‘thinner’ high-frequency overhangs audible, and the left and right channels are phase-coherent. The scale of the sound stage and the localization of sound sources within it can be perfectly determined.

The titanium dynamic driver paired with the QCC3040 chip used results in a fast, dry, but very significant impact even at low volume. Due to the high detail level of the armature emitters and the vivid and precise bass, the NFP sound very dynamic, engaging, way better than their wireless buddies.

As for the detailing, everything is simple here: an armature driver is an armature driver, after all. The default sound setting seems fond of larger musical images and a rustling upper-frequency range simulating overdetalization. When applying the equalization proposed, the ability of the NFP to transmit minuscule details surfaces — all virtually without emphasizing some specific parts of the sound range. Which, I’m noting again, is completely out of character for TWS headphones. And even when using a regular aptX codec, it doesn’t matter at all — there’s more than enough information for musical material playback.

It’s also worth noting that the exceptionally high level of maximum volume is here. Already at 80% of the volume, you feel a surge to shout ‘Enough!’, and the 100% will probably damage your hearing hands down.

Sound signature

Next, we’ll talk about the equalized version of the NFP sound. See the screenshot above.

The super-heavy and incredibly well-articulated sub-bass starts at 22 Hz already (for my perception, all right). Up to the 250 Hz, it’s completely flat, or at least doesn’t have any sharp rises or dips. The lower portion of the mid-frequency range sports a slight rise up to 500 Hz. Further on, up to 1000 Hz, no frequencies are accentuated individually. There’s a dip at 1850 Hz (which can’t be corrected by the equalizer, btw), a significant rise to 3 kHz and a smooth decline at around 4 kHz. Between the 4 and 6 kHz, the 4750 Hz frequency is emphasized. Then everything’s more or less even, except for the peaks at 7800 and 13500 Hz, which also can’t be completely corrected by equalization.

If all or almost all of the above doesn’t ring any bells with you, then here’s an explanation for regular humans: these headphones have slightly brighter sound features, they deliver the sound flow very close to the listener, and also try to take out the high-frequency trash from the above 10 kHz range. This is exactly how the hued sound gives a feeling of a very high-detailed musical material, although 60% of this is due to the tuning of the headphones’ frequency response, and only 40% of this effect is due to the quality of the speaker and the armature driver. For example, the saxophone would always somewhat grate on your ears, female voices would seem thinner, and the cymbals would be more highlighted in terms of volume and have a distinct metallic trace. But in any track, a feeling of airiness, space and volume is guaranteed.

All of this is applicable when comparing the NFP with some high-quality wired headphones.

As for the fully wireless headphones, I’d say the NFP deliver an incredibly balanced monitor-neutral sounding. Especially considering that the NFP’s fellows aren’t even able to reproduce the top upper- and bottom lower-frequencies. Yeah, it’s impossible to escape the obvious sharpness of the sound. You get some freaking deep bass levels in return — the bass that never loses its delicious texture, topped with a fairly smooth and detailed mid-frequency range, as well as those beautiful airy upper frequencies thanks to the fast armature driver.

It’s not a big deal to tell what kind of music would be the most suitable to listen with the NFP: this would be any guitar and instrumental pieces in general, any complex and also some lighter electronic music, some retrowave, synthpop, etc. You just try to set the first two equalizer bands to the default, and here you are enjoying all kinds of heavy metal — even the most aggressive ones. The NFP are proven to be one of the best headphones for such music, that’s it — confirmed by multiple metalheads among my friends.

Naturally, with such technical potential, these require some well-recorded musical material (you didn’t see that coming, right?), or you be sure to hear every single piece of crap, all the recording and mixing fuckups. And suffer.

Summary

The Noble aren’t novices in producing wired headphones, and I don’t doubt the company’s high expertise in sound equipment. The Noble TWS emerged on the market for the first time only in 2019, and I suspect the development of the software of at least the Falcon Pro (and maybe other company’s wireless headphones as well) was actually outsourced to… Let’s denominate them as amateurs (and this would be the nicest they’ve ever been called).

The sound delivery part — no questions here, the Falcon Pro are awesome on this side, they really are. As for the detailing, attack speed, micro-nuance reproduction, sound stage width and instrument positioning accuracy, these seem to bypass all currently existing TWS models, with the exception of Devialet Gemini and Final Audio EVA2020, which I haven’t tested (yet). I won’t even complain about the absence of active noise reduction, since the passive one is implemented just perfectly. Excellent ergonomics, well-designed included earpads — again, flawless hit here.

You want to know what’s bad about the Falcon Pro? It’s poorly elaborated use cases — user experience quality, if you like, and even wireless charging doesn’t save the day in this respect. The mobile app, as you may already have guessed, is somewhere very close to amateurish projects one could do between classes in tech college, and there’s nothing from a native software for a flagship product both in terms of functionality and stability.

In this sense, the Noble Falcon Pro’s concept is close to the world of audiophilia, where they often rely on sound quality, and other aspects of the product don’t receive due focus and are regarded as insignificant.

Consider buying the Noble Falcon Pro if all you need is good sound at all cost (literally, too). If you’re more into good and convenient software, active noise reduction and other smart features, take a look at the Sony WF-1000XM4 for the same money. Or maybe the radically cheaper WF-1000XM3 sporting almost the same sound quality as the XM4. Or another billion of other models featuring a whatever sound, but worth significantly less.

Well, the Falcon Pro is pretty much for anyone putting sound quality above usage convenience.

For guys like me, because you know what? I bought them.