Over-Ear Headphone Measurements: A Couple of Fine Points

I’m working on a ranking list of over-ear headphones and taking a lot of measurements. And, even bypassing the issue of its preparation, I’ve made a great many of these measurements over the past few years. The purpose of this text is to clarify some fine points that are not commonly discussed publicly in the community of fans of measuring something or speculating about the sound of headphones when looking at the available measurements. See, heaphones.com suddenly decided to speak out on this topic, too.

The questions are as follows:

- How exactly should over-ear headphones be measured?

- What affects the measurements of over-ear headphones?

- What additional information should be published?

- Can a measurer influence these very measurements?

- How do we move on?

What’s beyond the scope of the discussion:

- The issues of rig standards and comparisons of measurements at rigs of different standards. I have already discussed this topic in detail here.

- The issues of how well the measurements on the rig correspond to the actual perception of sound have been discussed here, too.

I’ll start, as usual, from the beginning – goal setting.

Why do we measure headphones?

I define the purpose of measuring headphones at different levels of goal setting as follows:

- to compare headphone measurements with each other and with target curves

in order to - figure out which ones sound better

in order to - make a reasonable decision about the purchase of a particular model.

This is an obvious simplification because headphones have a lot of other parameters, such as availability and price in a particular region of the world, availability of warranty service, convenience, sound source requirements, etc.

However, I’m going to talk only about sound now, that is, about measurements.

Sample choice

The very idea of representative measurement of the parameters of a headphone model implies a number of assumptions and omissions due to the fact that it is not the model that is being measured (this is generally a marketing construct), but certain physical samples. It is implied that:

- All samples of the same model sound the same.

- The sound of the same sample does not change throughout its entire service life.

As you know, neither the first nor the second statements are true in the real world.

There is a difference between the samples, and it’s significant, which has already been discussed a million times. This is due to the imperfection of the production process, the occurrence of so-called ‘silent revisions’ of the model (when the manufacturer intentionally decides to slightly ‘correct the sound’ for some reason), as well as due to attempts to cheapen/optimize the production process, when it is desirable to reduce the total cost of the product by reducing the cost of its components/production processes, as a result of which the sound slightly changes (the simplest example is replacing drivers with cheaper ones or moving production to another factory).

There is a problem with the second point, too: when drivers of different types seem to be (I’m not an expert) not very susceptible to aging over a distance of 3-5 years, then earpads are a different story. Earpads are half, if not 75% of the sound of headphones. With the routine use of headphones (on one’s head), earpads crumple, which leads to a change in their internal volume, a change in the distance between the driver and the eardrum, as well as a change in the density of the filler and blocking of a number of internal perforation holes of the earpads, if any. And this affects the sound up to one’s ears. Besides, here we need to think a little more: earpads of different headphones deform at different rates. Some immediately crumple and stabilize in this form for quite a long period, while others deform linearly throughout their entire service life. The question is, what kind of sound did the manufacturer expect to convey to the consumer? What sound should be considered correct? One with new earpads, with earpads in a ‘medium wear’ state, or with ones already well used? The question seems strange, but only at first glance: the earpads of DCA E3 or Fiio JT1 are initially quite plump and dense enough that, for example, with new samples of these headphones, a sufficient air gap appears on my head so that these headphones lose a significant part of subbass. And this is definitely not the sound the manufacturer was hoping for. Over time, after N hours of use, the situation improves, the earpads crumple slightly, and the headphones fit snugly.

Thus, in an ideal world, a reviewer/measurer should select several samples of the same model for measurements (the more the better), and those produced relatively recently at that. And these should be new samples, identical to those that ordinary people acquire. They will provide measurements of the sound that users will receive immediately after purchase. And then there should be a number of samples of kind of ‘the same revision’, but used: their measurements will make it possible to understand how the sound will or will not change with the degradation of earpads and drivers, if any.

This was a description of an approach in an ideal world.

In the real world, it would be great if a measurer tried to get at least 2-3 samples of the same model, with one of the copies surely new. I’ll tell more about the earpads below.

Measurements: the position of the headphones on the rig

We are not talking about the earpads yet, but only about the position of the driver in relation to the ‘rubber ear’.

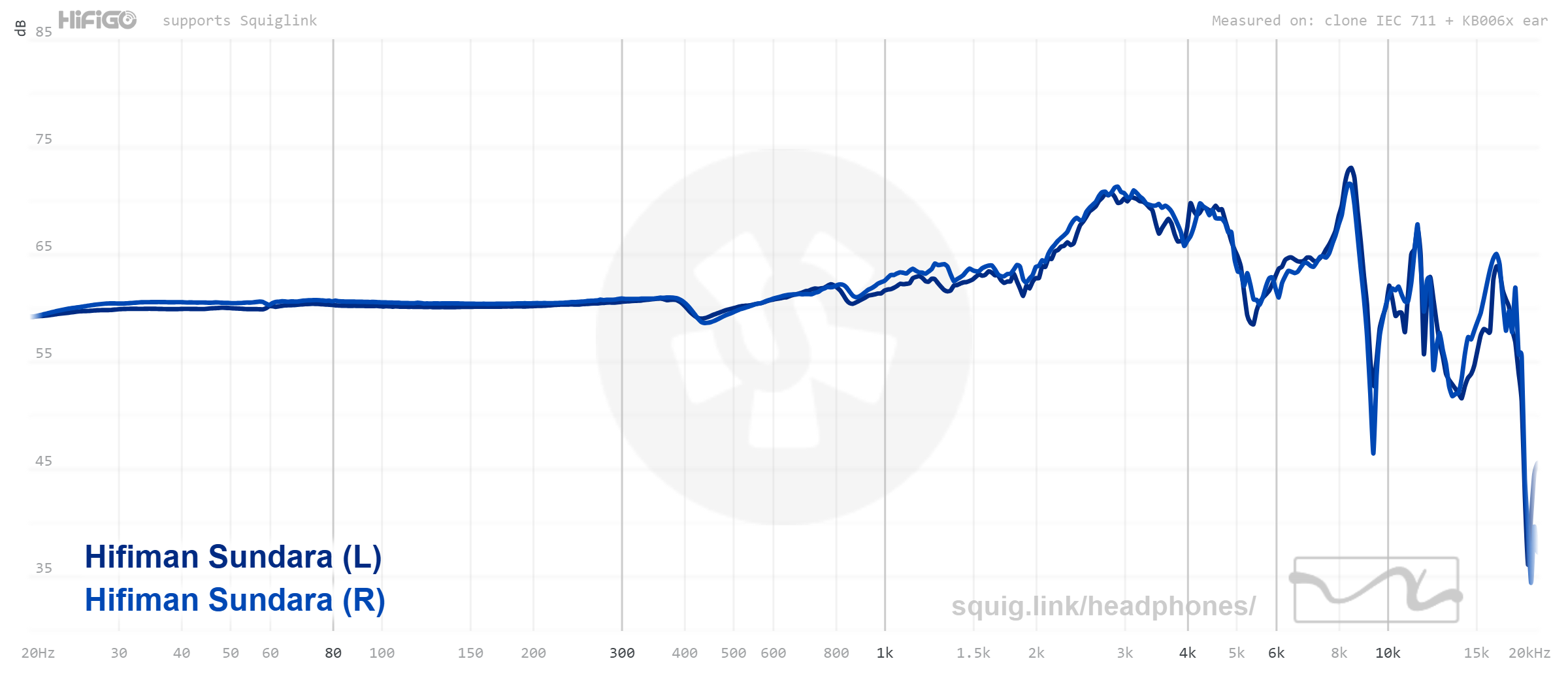

The key statement is not new: the sound of headphones strongly depends on their position on the head, and the measurements depend on the position of the headphones on the rig in the same manner. Any rotation, shift, or their composition is guaranteed to change the sound and measurements. There are exceptions such as HiFiMan Sundara, but they are extremely rare. Please note that if a driver is positioned at an angle, the differences will be really radical.

Consequently and in the great scheme of things, it’s necessary to measure not in one position, but at least in seven:

- standard position;

- turning backward;

- turning forward;

- backward shift;

- forward shift;

- upward shift;

- downward shift.

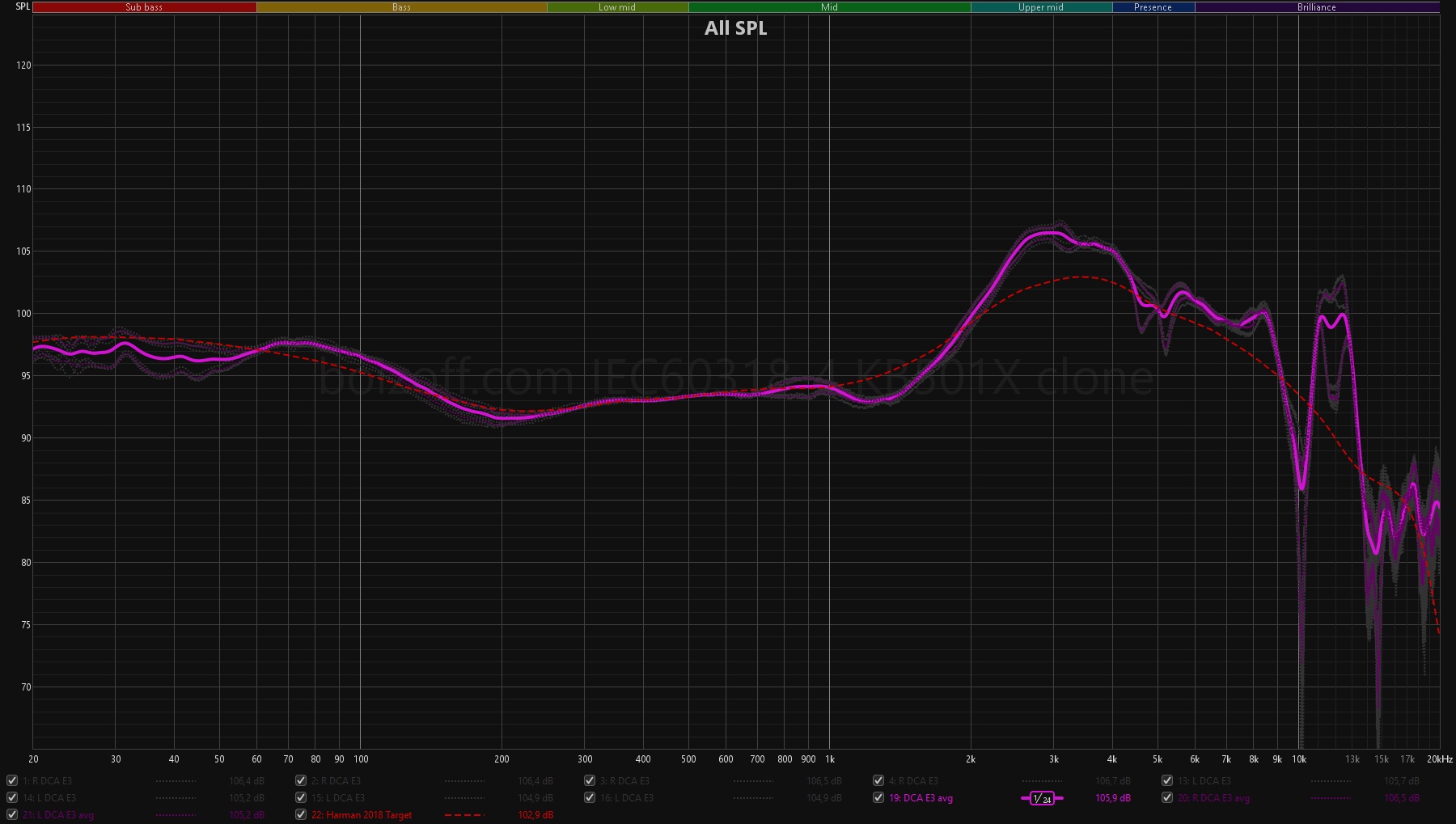

And then there are combined options, such as ‘a downward and forward shift when turning back’. I’m gonna reveal an incredible secret of all secrets: if you measure the frequency response, then simply lift a headphone and put it back on the rig, trying not to change its position in any way, then the next measurement will differ from the first one because it is impossible to position the headphone on the rig twice in exactly the same way. Therefore, diligent measurers do not take one measurement in one position, but at least five for the left and right headphones separately and then take the average value. In my measurements, you can see gray lines on the graphs – these are those frequency response variations in the same (sort of the ‘same’) position.

If we talk about an ideal world, there should be 7 positions at least, with 5 measurements for the left and right headphones separately, which would be 70 measurements in total, plus compositions of shifts + rotations.

The reality is somewhat less harsh: many headphones do not imply variations in their fit. Take, say, RØDE NTH-100 – their earcups are literally made in the shape of the ears, so you can’t turn or move them on your head anyway. Alternatively, the space inside the earcups can be just small enough (see Simgot EP5 or Fiio FT3) to eliminate the possibility of at least linear shifts. But as for some models, such as DCA E3 or HiFiMan Edition XS (of this entire line), you’ll have to ‘fuck hard’.

Measurements: earpads

We continue the topic started above about the wear of earpads and measurements.

Ideally, we need to take measurements with earpads which ‘grades of freshness’ vary. But if it can’t be done (and it can’t in 99% of cases), then it would be good to take measurements at least with different pressures, as if simulating the wear of the earpads.

But even when earpads are new, there’s a catch: you take one measurement, then the next one after a minute, then one more in 5 minutes, and you don’t touch the headphones at this time, but the measurements may turn out to be slightly different because within these 5 minutes the earpads have crumpled to their ‘working’ state. It will be the same when on the head. Therefore, reasonable people don’t take measurements immediately, but after some time after placing the headphones on the rig. You can just try to press them with your hands, but this is not okay: you can press harder than you need, and you can also damage the driver.

Another story is beveled earpads. When working with them, you need to remember that the headband should pull the headphones towards the rig plate not at a right, but at a shallower angle. And there is also a high probability that such earpads will shrink more in the front, where they are thinner, than in the thick back. But not always. Therefore, it would be good to verify this statement practically, that is, by wearing them on your head before taking measurements.

One more point is about memory foam earpads, such as ones Sony WH1000-XMn have. This foam is impregnated with a wax-like substance that becomes less viscous when the earpads are heated from human skin. And the rig, be it a metal plate with a silicone ear or even a whole ‘head’, is not equipped with a heating system. Therefore, when working with earpads of this type, it is necessary to guess to wear the headphones on a living, warm head first for a while so that they are realistically deformed, and only then to place them on the rig.

Another common problem is attaining a fit that eliminates air gaps. This problem is not even a thing in itself, but combined with a more complex question: what was the manufacturer actually keeping in view? Were the air gaps supposed to be the case in real use? As for me, I’m kind of ‘lucky’ — I have a completely bald, shaved head of a pretty ordinary shape, but quite a large one, and I don’t wear glasses. Almost any headphones fit on my head ‘without any holes’. But, on average, people are more likely to have hair than not, and some happen to have glasses, too. How should this all be communicated to readers through graphs? By means of differentiation of measurements: with an ideal pressure, then with a tiny gap, and also with a gap of a ‘glasses arm’ type.

And the last question is the effect of earpads on the sound in terms of a particular pair of them. For example, you can see that the channels are diverging. Is is about faulty drivers or earpads? It’s easy to understand that: we need to take measurements in any position, then swap the earpads and measure once again. If the difference between the channels persists, it’s about the drivers. If not, the problem is in the earpads.

Measurements: cable

This is a rare case, but I’ve seen it with my own eyes: the cable was so crooked, and the left and right channels were so different in impedance that it caused a significant (more than 2 dB) discrepancy. Therefore, one should not be lazy and measure the left and right headphones on the same channel.

And then it’s time to try not to get confused in our own measurements.

Measurements: frequency response and room

Yes, ‘room’. I mean it. Look at these measurements:

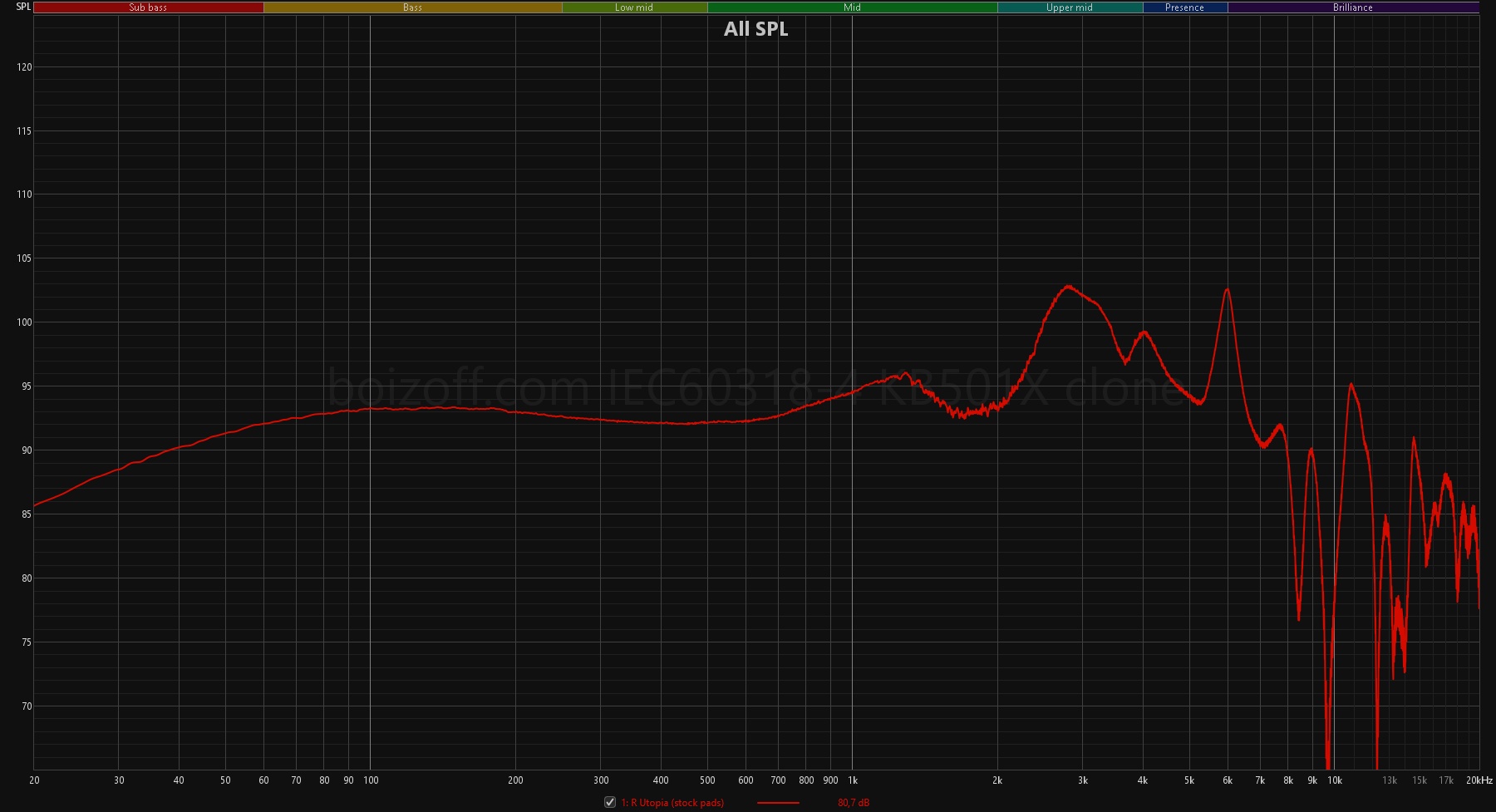

Do you see some sort of ‘saw-like’ frequency response fluctuations in the 1-3 kHz range? These are re-reflections of sound from the walls and ceiling of the room. The more open the headphones are, the louder they play outwards, the more pronounced these deviations will be. This effect is clear and apparent, and it can be seen in multiple measurements at squig.link:

Why did I think it was about the room? It’s because I found a simple way to deal with them, with the help of a ‘pillow fort’. Just see the measurements:

I stacked two pillows like a fort over the headphones so that the pillows didn’t affect the pressure and didn’t touch the headphones at all:

In an ideal world, ideal measurements should be made in an anechoic chamber. In the real world, we have only ‘pillow forts’. At least, I have.

Let me note that there’s no harm in it: the IEC 60268-7 standard suggests using 1/3 octave smoothing, which will smooth out such deviations completely. Personally, I (as well as progressively-minded representatives of the Western community) believe that it’s necessary to look at the frequency response in much more detail, using 1/24 or at least 1/12 octave smoothing.

Measurements: distortion

There are three factors involved.

Firstly, distortion can only be measured with a calibrated microphone. And for this, we actually need an acoustic calibrator. I wrote about mine here. I mean, it should be listed in the description of the rig; otherwise, it’s not clear where these 94, 104 or 114 dB of volume, which are used to measure nonlinear distortion, come from.

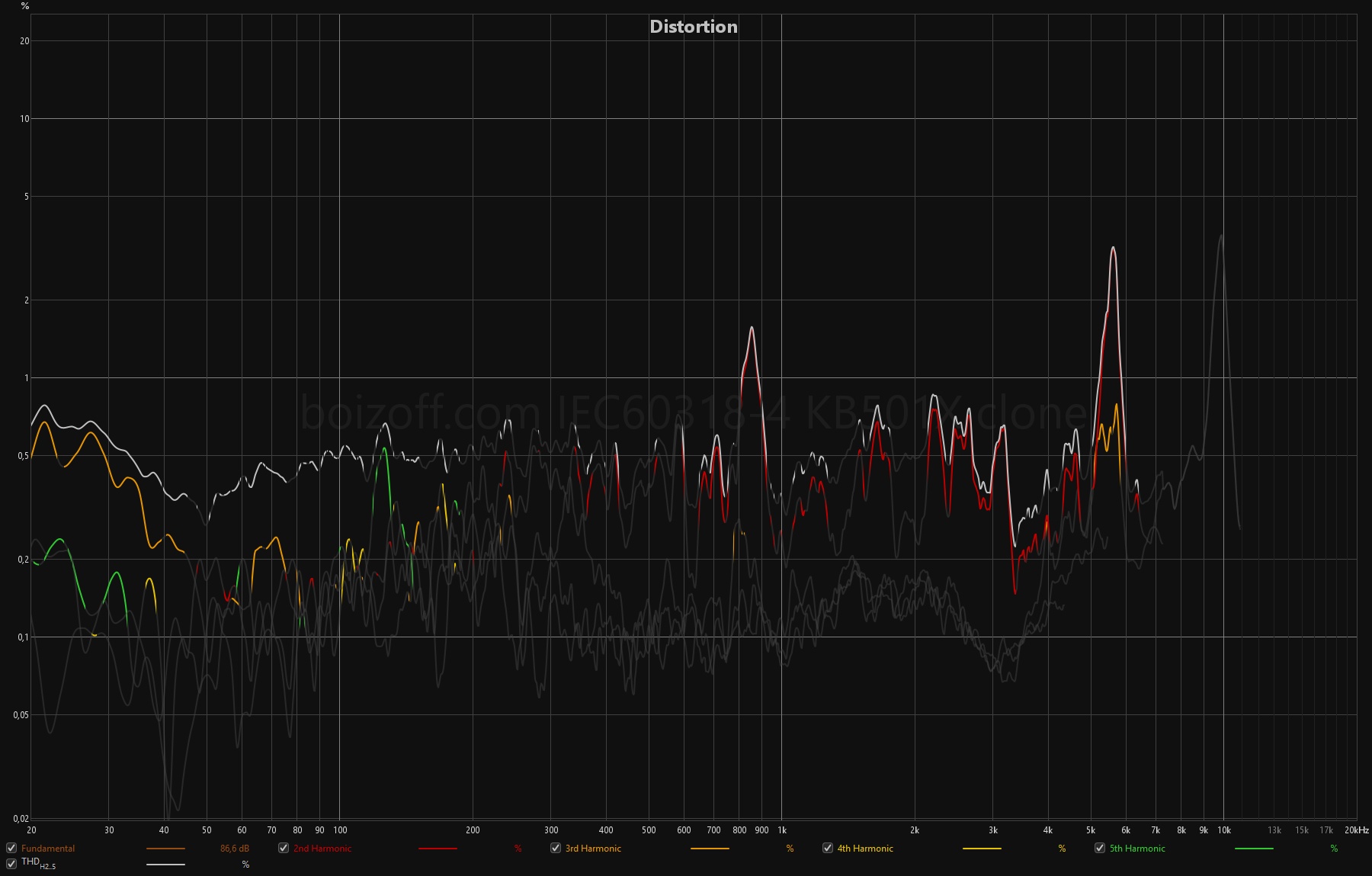

Secondly, distortion measurements are influenced by external noise, especially if the headphones are open-back. Here are two measurements (of the same headphones, of course). In the first case, the external noise level is higher; in the second one, it’s lower. Look at the distortion in the 50-500 Hz range.

Thirdly, low-frequency vibrations are transmitted through the surface, on which the rig is located. In an ideal world, the rig should be not only in a soundproof anechoic chamber, but also on a vibration-absorbing suspension. In the real world, we can build a small measurement box (in one of his old videos, DMS suggested using a noise-insulated PC case for this, IIRC). I’m getting along pretty well without it.

The basic idea is simple: the level of external noise should be low (ideally, up to 0.2%) and should be shown explicitly on the graphs. In my pictures, it’s a brown curve labeled as ‘Noise floor’.

What information should be published in the measurements?

From all of the above, it follows that measurements must be accompanied by a lot of additional information to make it clear what exactly, how, and under what conditions has been measured. Primarily, it’s about mentioning the rig standard, smoothing and everything that I wrote about in the Conclusions section here, so I won’t repeat myself.

Each measurement should be an average of at least 5 measurements of headphones taken in the ‘same’ position.

For each frequency response measurement, we specify the following:

- year of purchase/production of the sample;

- serial number of the sample;

- model of earpads;

- pressure/degree of wear of earpads;

- position of the headphones on the rig;

- time during which the sample was used (the degree of wear and tear, so to speak).

For each distortion measurement, it is necessary to explicitly indicate the level of external noise, as well as the presence of an acoustic calibrator as part of the rig equipment.

Moreover, it is desirable to measure not one, but at least 3 pairs of headphones of the same model.

That is, in a strict sense, in order to be able to say with conviction, “I MEASURED THEM!”, it’s necessary to make some 200 measurements. Not only will there not be enough time for this, but the results will also ‘lose their edge’ and cease to be relevant as soon as the manufacturer decides to change anything in the sound of the model.

Influence of a measurer, as a human being, on measurements

It’s not difficult to guess that, by virtue of all the above, a measurer can influence the measurements both indirectly and directly.

Indirectly, it’s about not paying attention to the details: the condition of a particular sample and earpads, the nuances of the position of the headphones on the rig, the pressure, etc.

Directly, that is, to intentionally distort the results, it’s about the use of earpads other than the original ones, changing the angle of the headphones on the rig, some other manipulations… And if you really want to, you can just adjust the sound with an equalizer and not tell anyone about it. This is much faster and easier than fiddling with the position and pressure, for example.

And the key question is, how do we determine the measurement quality?

A simple, absolutely correct, but useless answer is to take the same (literally the same sample) headphones and measure them personally on the same rig. A difficult answer is to analyze many measurements of different headphones made by the same person, to compare them with different measurements of other measurers, as well as with your own auditory experience, and to come to a conclusion therethrough whether these measurements can or cannot be trusted.

And, well, a measure of quality assurance is the fact that the measurer understands the whole shebang and publicly demonstrates their knowledge by publishing similar articles, measurement regulations, as well as accompanying their measurements with all the necessary information. Whether they adhere to their own regulations can only be assessed implicitly.

Summary

If you think that this text is written as my own apology, it’s not true, and you are mistaken. Obviously, I know all these nuances, but I don’t always manage to keep the information complete and the measurements accurate: I am a living person, time-poor and on a budget. What I’m doing is far from perfect, and it could be much, much better. That’s why, for example, I take repeated measurements of headphones and update my database: sometimes my skill becomes better, and other times I’m in doubt in regard to some samples.

Does this mean that any measurements are useless? No, it doesn’t. If they are based on decent samples, performed by a competent expert, and accompanied with appropriate comments, then measurements indicate the sound much better than ridiculous piles of freely interpreted epithets such as ‘high detail’, ‘low resolution’ and others. I’d like to note that everything that was written about the samples, earpads and the position on the head before also affects my personal, subjective listening experience. These are universal factors.

Lastly, the task of preparing an up-to-date rating of over-ear headphones in the context of what has been already written acquires additional value: I use only new samples from the middle of 2025, which I began to explicitly indicate in the measurements at squig.link (not everywhere yet, but I’ll correct it). In other words, it will be an actual juncture for 2025, made by a single person, and not a hodgepodge of fuck knows what, measured fuck knows when and how.

I hope it was helpful.