About audiophilia and melomania, Meze Empyrean and RME ADI-2 DAC

I love music: I have listened to it since I was just a kid, and I do it a lot. And with a lot of passion. Music isn’t just ‘important’ for me: it still sends shivers down my spine, and I couldn’t control it even if I wanted to. The thing is that the music actually controls me.

I remember falling asleep to Pink Floyd and Toto Cutugno (you only may know Toto Cutugno if you’re Italian or Russian of at least 25 years of age) when I was 4 to 6 years old wearing those vintage Soviet Amfiton TDS-17 headphones. Then I graduated from the piano class of the music school, went to Bach organ music nights in the City Philharmonic Hall with my parents and did many other academic music-related things when I was younger. As I grew older, my musical taste evolved with me: starting from those very first post-Soviet pop bands and Scooter and the so called Russian rock, passing through Placebo, Portishead and Marilyn Manson and ending up with growling metal, industrial and howling delta blues. By the age of 25 I realized that the fact of liking one or another genre doesn’t actually say anything about a person except that the person is tunnel-visioned. In fact, there’s no bad genres (let’s not mention Russian rap or Russian chanson, these are objectively worse than anything you’ve even heard in your lives), there’s only bad music and good music. Regarding the good one, you can find it in any genre, you just need to learn how to listen to it and to perceive it.

As incredible as it may seem, I’ve always been looking for good music and not equipment to make any track sound better. My musical ‘growing-up’ happened in the first post-Soviet decade, when you had to decide whether you want to have some decent sound while listening to the music or to have something to eat (no kidding, these were tough times in Russia). Obviously, most people including me chose the physiological over the aesthetic.

That’s why I was more than happy listening to the music via cellphone and the headphones provided with it, until I met them: the in-ear Fischer Audio DBA-02 mkII headphones. After the very first time I used them I discovered that the music can actually sound differently, even somehow unearthly. It was wide, bright and very detailed.

So I dug into frequency response, square waves, output impedance and other specs and started to look for my own perfect sound, that special combination of devices to make the music sound just like I love it: as if the band performed right in my room, and a little bit better. Then I started trying different cables, earpads, portable players experimenting with their firmware etc. I ultimately found my perfect sounding after 7 years of stubborn searching. To be more precise, it wasn’t a perfect sounding or perfect equipment, it was an approach that spared me all this typical audiophile drama.

That is, this post is for those who want to know how to find a decent sounding and skip years of information digging. To be honest, I’d give anything to have somebody give me this post on a silver platter at the very beginning of my journey.

Here are the 3 main principles to remember when building your own sound system.

First:

don’t ever be strictly subjective

The ‘listening’ thing is a chain of elements, and those are – sound source, cable, speakers or headphones, our ears and ultimately our brain. The latter is the most unreliable and unpredictable element among them. Our brain may perceive sound (or, in other words, the information provided by our ears) differently depending on the time of day, degree of fatigue, mood, background noise and a pile of other factors. It may even depend on the design or cost of your sound system. That being said, the same track can actually sound differently when you’re working your ass off during workout or relaxing in the backyard, when you’re fresh and energetic or sleepy, at the dawn or in the evening, when outside (and the part of the frequency band is concealed by the street noise) or in absolute silence at home.

Now let’s talk about ears — they’re obviously different for all people, both from the outside and from the inside. That is, not only the auricle is curved in each person’s own way, but the ear canal has different shapes in different people. Of course, there are more or less similar general characteristics, common for all Homo sapiens — for example, the resonance at a frequency of about 2000 Hz or the audibility threshold from 35 Hz to 17 kHz. But otherwise, the perception of frequencies within the audible range varies quite significantly from person to person.

Moreover, at the same sound pressure (volume), we subjectively perceive the volume of different frequencies in different ways. To dive into the topic, you can google the Fletcher-Munson curves: you will learn that the louder the sound, the more the curve resembles a straight line, which means that at any higher volume, lower and higher frequencies are perceived much louder. Important: when listening to anything, the volume of sound plays a huge role and directly affects how the frequency balance is perceived by your ear.

In addition, different people have different thresholds of perception comfort at different frequencies. For example, a 40 Hz 50 dB sub-bass sound may throw some uncomfortable pressure on you but would be perceived as dead silence by your friend. The same applies to upper frequencies. The left and right ear can hear differently: there is usually a 1-2 dB bias between the ears at different frequencies in different directions. If you are curious to find out what’s your case, do an audiometry test.

Here’s my preliminary conclusion: different people hear sooo much differently. So when you read online reviews about headphones or any other sound equipment, pay special attention to whether the author has given a hint about the listening conditions and/or provided reference to his or her other reviews, so you could better relate their perception to yours. If not, the review is useless, close the browser tab.

Second:

all hardware parameters are measurable

As a person with a technical mindset and a technical background, I won’t even start on all that nonsense about ‘reverberating’ wooden cable holders and harmonizer systems. Let’s make it clear:

- The headphones’ sounding can be perfectly characterized by two parameters: the frequency response and the waterfall. The electrical specs of headphones can be described by two other parameters: the average resistance and the average sensitivity.

- The output (source) sound (DAC + amplifier) is characterized by the frequency response graph, the noise level, the spectrum and the amount of harmonic distortion. And maybe, just maybe – by the interchannel penetration phase. The electrical specs of an amplifier can be described by the maximum current level under different loads and its own resistance.

This one is a very simplistic scheme, but still applicable to 99% of cases. Now, the cables. Let’s make it clear – the cables don’t sound, and they don’t affect the sound in any way. Only if you buy some real cheap shit, then you might be in trouble. But otherwise, there is no such thing as a better sounding cable. Cables don’t have a direction, either. And they don’t change the sounding, even if you wrap them up in toilet paper or embalm them in snake oil, period. The only thing that matters in any cable is its resistance, which is always negligible compared to the resistance of the source. No skin effects affect the sound in any way, even if they are there and can be measured. Any special sound-transmitting electrical particles can flow perfectly along any cables and in any direction, and transmit sound in exactly the same way (with the properly manufactured cable).

If someone tells you that there is a sound difference in technically identical hardware, then that someone is either wrong, or the measurements were incorrect and the figures are actually different, or the measured parameters were chosen wrong. For those who want to dive into the amazing world of dumb researches, here’s a link to an oh so long list of documented – and undoubtfully failed – attempts to hear the difference between power cables, interconnects, HDMI cables and other bullshit. You can also check some great examples, when people can’t tell the sound of different speakers and amplifiers apart (let alone the damn cables) in a blind test, and – just wait for it – can’t pick up the difference between a recording and a live performance. Do you think they’ll be able to hear the cable? Me neither.

Third:

in terms of ‘sound quality’, 90% depends on the speakers/headphones, 10% — on the sound source

The scary truth is that it’s really difficult, almost impossible to find a really bad (with downright shitty measurements) sound source, DAC and/or amplifier nowadays. Even the low-cost and a bit obsolete smartphones are phenomenally good in what’s related to the above-mentioned sound parameters — see the example here. The same applies to modern external sound cards, even gaming ones — see the example here. That is, if a ‘source-headphones’ combination is lined up correctly, and the electrical parameters of the hardware are chosen wisely, then the sound will be coloured 90% thanks to the headphones and 10% due to the source quality. And this is why you don’t find stupid discussions, if someone on a decent international audiophile website says they pair their Campfire Audio Andromeda with iPhones, or Noble Kaiser 10U with a Samsung Galaxy. However, if you dare come across a tedious nesting crawling with pathetic audio visionaries, the mood changes completely: you will see discussions on music players and how they ‘reveal the potential’ of different headphones, done in model-by-model style, and the discussion will be blood and guts. And don’t ever try start the discussion on cables. Just don’t.

To avoid any misunderstanding: sources may sound differently. However, in order to actually hear the difference, you need to have a very trained ear, listen critically and pick some very special tracks. Along with that, if the sound from different sources differs radically, when listened on the same pair of headphones, it could mean just two things: that either the electrical parameters of those sources are also radically different, or that you’re listening to the music at different volumes.

Now, let’s summarize:

- When evaluating the sounding of the hardware, don’t rely on the I-kind-of-seem-to-hear-the-difference feeling, avoid doing comparisons from memory and don’t on hold on online reviews.

- If there’s a difference in sound at all, it’s always measurable. If there’s no difference in measurements, but there’s an audible difference — then it was just a feeling, trust the figures. Or you’ve measured wrong parameters. Or you’ve measured them incorrectly.

- In any source-headphones/speakers combination (provided they are compatible on electrical level), 90% of the set-up depends on the headphones or speakers and 10% — on the sound source. And talking about the speakers, the acoustic design of your room (or its absence) contributes at least 40% of those 90%.

Now let’s get to the main thing:

the choice of your ‘sound’

There are two fundamentally different approaches here.

The first one is based on one’s subjective perception: do you like it or not, does it sound natural or not, does it sound like it should or not. The wordings speak for themselves, that this principle is weird and judgemental, and any judgement can be effected by billions of different factors. For instance, you can go to a store, bring all the music you need with yourself, spend two or maybe even three hours on meticulous listening. And immediately you will be forced to accept, that:

- You have to turn up the volume to actually hear the music, because of the background music in the store, all other customers buzzing around and stuff like that. And what if you wanted to try out a pair of open headphones?

- You came for a pair of headphones, but you did not bring the source you’re using at home. So you had to use some random source at the store, which does not come even close to the specs of your home one.

- You came to the store, but it’s been a long busy day, you are tired and hungry, and your mind is not thinking clearly.

- You’ve narrowed down your choice to a couple of models after reading reviews by some audio guru (sure, they can’t be wrong). You did not find any measurements, your listening experience was a fail, and yet you think – that guru couldn’t be wrong, right? And you just have to get used to the sound.

So, you buy the thing, and just a couple of days later you become painfully aware that it’s not ‘your sound’. It sounded somehow differently back at the store: it was brighter, more emotional, more energetic. On top of all, you realize that the headphones are too heavy, there’s too much pressure on the top of your head after 30 minutes of wearing, and – let’s be honest – they can’t just stay put on your head.

After a week of using, you clearly realize that you’ve made a huge mistake. But you barely have the courage to admit this, and there again are those numerous positive reviews all over the Internet. Therefore, the next cycle of purchases begins for you hoping to build a ‘balanced audio system’ where ‘all the components are on the same level’, ‘release’ the true sound, and so on. You can’t hear your music anymore, since you only need music to check the new piece of hardware for your system. And just wait for your progressing neurosis to manifest itself, and the disappointment to start building up about your choices, that push you into having pointless and heated discussions, where you fight your ass off to defend your choice being the only correct one. Especially if no one asked your opinion.

Congratulations. You have now become a true audiophile. That’s official. An ‘audiophile’, and not in a good way.

The second approach assumes that the main purpose of any sound equipment – is to provide accurate reproduction. In other words, it should play music exactly how it was recorded. To the very last tone. This approach is also a long road of suffering: you’ll immediately discover that the vast majority of music is recorded poorly — with overload, murky highs, resonances, narrow soundstage, small dynamic range, and so on. And only a fraction of all the music out there is actually recorded and mixed up to a standard, making it worth listening via good equipment. Good equipment becomes that surgical tool, which enables you to meticulously dig into the guts of a track, And the sad truth is – the insides of most music tracks are not worth taking a closer look at.

Through much suffering comes wisdom – now you can at least be sure, that you hear exactly what was recorded and just the artist intended. So if you don’t like what you hear, you don’t blame it on your audio set-up, since you know exactly what your system is capable of. You have looked up the frequency response, the waterfall and picked up a suitable source in terms of power and other parameters. You are already beyond the esoteric search for ‘sounding’ cables and holders; you just listen to different music and find out – quite (un)surprisingly – that music can be different, and you may like it or not. On the bright side, though – you finally listen to music, and this is good news. And your audio equipment is just a precise tool, that brings your music to your ears as the artist intended. In a sense, you should not pick equipment to suit your liking. Rather, the equipment is there to educate your hearing.

Now, since the subjectivity is still there, and there is no chance to get rid of it, it would still be great to have the means to vary the sound. For example, in the evening, when comfortably at home, me and my glass of 10 years old Hepburn’s Choice’s ‘Nice’n Peaty’ 2006, I like my music lighter and snappier. And in the morning, before work and if in a bad mood, I like it when the good old Limp Bizkit’s ‘Nookie’ with raised bass truly blows the sound into my face.

Let’s summarize again. The equipment should:

- ensure maximum accuracy of reproduction;

- offer some options to adjust the sound to the listener’s ears and their brain;

- ideally, it should also offer hardware analysis capabilities.

And at this point it’s time we talk about some real hardware pieces: the Meze Empyrean headphones and the RME ADI-2 DAC integrated headphones DAS+amplifier.

Meze Empyrean

(or referred to as ‘ME’ in the text below).

I am intentionally skipping the design features, since these are headphones, not a fancy vase. What’s important is the comfort of them sitting on your head. These headphones have an expressly simple design. The main frame is made of carbon fiber and a wide leather headpad which is actually touching the top of your head. The frame is extremely flexible and attached to the earcups hinges. The earcups are made of aluminium, they rotate freely around the tubes they’re attached to. You can also slightly pull them by a small angle up and down. Thanks to this headpad, the hinges, and those awesome thick earcups, the headphones sit on your head so comfortably, you’d hardly believe it. You can wear them for 8 hours straight, and even after that you won’t feel any pressure or experience any slippiness. The open back design allows some airflow around the ears, so the skin doesn’t sweat.

In my opinion, these are the most comfortable headphones out there, whether you have a bigger or a smaller head.

The headphones are manufactured with sky high quality, the parts are CNC-cut from aluminium, and assembled by hand, which are obviously not all thumbs.

The headphones feature some cleverly built isodynamic drivers, which are designed specifically for these headphones and play different frequencies with different parts of the membrane.

I won’t pretend that I actually understand the true odds of such design is: I’ll just say that I can fit the headphones as I like around my ears (positioning them lower or higher) — and it does not create any difference. The membrane is smaller than in Audeze LCD-4, but still huge: 102 x 73 mm. Which indirectly suggests the ability of the headphones to produce low-frequency sounds even at low volume. I’ll talk about it later on.

Electric specs:

- the average sensitivity in the 100 Hz–10 kHz range is 114 dB/V;

- the average resistance in the 40 Hz–15 kHz range: 32 Ohms.

In other words, those drivers should be able to rock even when paired to any modern smartphone. For example, when used with Galaxy S10+, the sound is perfect. The only thing to remember is the source resistance: the closer to zero, the more the left section of the frequency response bends down by -4 Db, and at a resistance of 20 Ohms, the response from 200 Hz and below flattens (see the link to the measurements below). The wires are connected to the headphones by 4-pin miniXLR connectors, the same as in most of the older Audeze, Kennerton and ZMF Verite. A cable with either a 3.5 or 6.3 mini jack, or a balance XLR is included. The manufacturer also offers some improved versions of these cables, but the price is ridiculously and outrageously high. So I bought a 1.5 m long 6.3 cable at Kennerton store for like $119.

There are two pairs of earpads included: velour and leather. The sound between the first and second differs quite significantly: the velour one has wider soundstage with more higher frequencies, and the sound itself is quite airy, and the leather one features narrower soundstage with equal portions of all frequencies. Below, I’ll stick to describe the sounding based on the leather earpads.

So, the sounding. You can simply look at the measurements. Or, if you like it verbalized, the main thing about the ME can be summarized in trivial words: for my ears the sound of these headphones possesses nothing special. I mean, there are the Sennheiser HD800 featuring the huuuge soundstage — like in no other headphones. But their 8 kHz peak is so pronounced, that you wouldn’t be able to listen to them for a long time. Or try Focal Utopia: their sound is so detailed, it just blows your mind off. Their bass on the other hand is ethereal and shy, and the 6 kHz curb gives the sound a particular colour. And let’s just skip the ergonomics and the weight of the headband. Or you could take Stax SR-007 Mk2 with their airiest highs in the world. But, they have a linear (!) rise at -20 dB in 20 to 90 Hz range. That is, don’t expect any sub-bass. In other words, the sound of the ‘ordinary cutting-edge’ headphones a few thousand bucks worth is usually estimated as something like 7-8 points out of 10 in all, but the soundstage/bass/lower frequencies/etc is straight 12 out of 10. In addition, such headphones have a noticeably excessive curb in the upper mid-frequency range. I think it’s because they’re expensive and mostly attractive for people at the age of 45 and older, who already have an age-specific hearing deformity — the sensitivity for the upper mid-frequencies decreases. These headphones are also good to create an impression of detail.

The ME’s sound is free of such peculiarities, they don’t have this higher frequency curb — so, these are the headphones for the young and wealthy. I’d rate them 9 or 9.5 out of 10 for all parameters. They won’t give you an extraordinary soundstage, super detailed sound, mind blowing bass or feathery airiness. They are just good. Very-very-very good and consistent for any aspect of sound. And I’ll say it again – they have phenomenally good ergonomics. Naturally, I’ve spent a decent amount of time comparing ME and Focal Utopia (which were my original pick), Audeze LCD-4z, MrSpeakers Voce, HiFiMAN HE-1000 V2 and some other less impressive products before buying. And in a direct comparison, at the same volume and on the same music samples, I got the impression that all models except for Empyrean, are designed to evaluate only one of the selected headphones’ sounding aspects. Emphasizing the ‘headphones‘, I really mean it. But the ME are different: they don’t exert their own sounding features, they are fully focused on the listening experience. The sound quality and comfort are unquestionable, too. But the emphasis is on the music, not the hardware.

So, in summary, the genre agnostic and versatile Empyreans are a step towards being a true melomaniac, while the above mentioned models are for the audiophiles, where you buy the whole bunch of those in one go – one pair for listening jazz, another for heavy metal, and a separate pair just to enjoy Led Zeppelin. This genre versatility of the Empyreans, their absence of any nuances, made me stop searching for the ‘perfect’ sound and finally pick ME, and after 4 months of using them not only have I zero regrets, but also can’t stop being amazed by those headphones. As an avid gamer, I can’t fail to mention the sound of MEs in gaming: it’s gorgeous as one should expected. When playing the notorious ‘Escape from Tarkov’, I can hear just the same amount of sounds as I usually do wearing my standard Sennheiser GSP 670 gaming headset at just +30% of volume up. Actually, if you stick a ModMic or ATGM2 mic to the ME, and you’ll get a perfect headset.

One more important thing about ME: these are the very first Meze Audio’s headphones of such sound quality, price and overall level. To be precise, Meze Audio have actually only 4 other headphones models (not including some mods). So, when there is such background, and the company wants to make a strong statement on the market, entering the premium segment on top of all, they work really hard to succeed. They want everything to be pitch perfect and slick to make themselves a name. This was also the case of iBasso SR01, by the way. You may ask here: but what about years of experience, know-hows and insights? Are they not the key to success? Well, to be honest, Meze Audio does have the experience. The diaphragms themselves were created (or just designed, there is no clarity into this question) by a certain Rinaro company, which in its turn is a Ukrainian Lviv based team (originally a Research institute for household electronic equipment spin-off). There’s more to it: this Research institute created that same soviet isodynamic Amfiton headphones (yes, the same headphones I used to listen to Pink Floyd when I was a kid). That is, these guys deal with membranes for an impressively long time. It would also seem, that the very same bunch of researchers contributed to the Oppo PM-1/2/3. Well, even if they didn’t have any experience nor proven practices: if a company already has a name, it’s actually more profitable to sit tight releasing slightly improved designs every year, and not to sink money into the R&D in an effort to produce something unique and decent in terms of quality. But if a company does not yet have a name, then they just need to bend every effort to create an outstanding product and take their spot on the market.

So in a nutshell, I’ve tried on Warwick Acoustics Sonoma Model One and Sennheiser Orpheus HE-1, wasn’t so lucky with HiFiMan Shangri-La, but the ME already became the final stop in my long journey – I can’t hear any dramatic difference between the insanely expensive products and the ME, and speaking the ultimately-the-best-in-the world Sennheiser Orpheus, their price of over $55,000 is just not something I would ever consider.

Now let’s talk about the source:

RME ADI-2 DAC

(or referred to as ‘ADI-2’ in the text below).

Here are three statements to consider, and you can stop right there if you wish.

- Phenomenally good measurements: here and here, at the very least.

- Small size (meaning, it’s convenient to use) — 215x52x150 mm, and nothing but digitally cold and perfectly engineered filling.

- Tons and tons of different options, including parametric equalizer for left and right ears separately, crossfeed, mid-side decoding and other stuff you didn’t even know existed.

The RME clearly has nothing to do with the audiophilia universe with all their cable fairies, animate chips, sound spirits living inside hardware and other bullshit. RME means studio equipment and real figures and parameters. To begin, let’s take a look into the user manual. Not only will you find a list of all parameters, graphs, measurements and flowcharts, but also each setting or option is described thoroughly in each corresponding separate section: you’ll know why a setting is important, why it’s usually used incorrectly, how it’s implemented in ADI-2, and why the way it’s implemented is the correct way. Just imagine, they’ve even included the IR-remote’s specs!

As a technical writer, I know that this amount of information is given when the companies know everything about the product, they’re 100% sure it works as intended, and are proud of it. You can actually use this manual as a guide to digital sound, since it’s all structured, detailed and easily understandable.

Now let’s take a look at the device itself:

- rear USB-port, coaxial and optical inputs;

- rear RCA and XLR outputs;

- front 6.3 output for ‘bigger’ headphones and a 3.5 one for ‘smaller’ in-ear headphones.

For specs, refer to the user manual or measurement reports. I’d like to emphasize the 0.1 Ohm impedance for both headphones outputs, as well as 1.5 W of maximum power for the bigger jack and 40 mW for the smaller one. Ultimately, you can use any headphones (except maybe some 600 Ohm ones). For example, the HD800 (430 Ohm) work just great, and the ME sound great connected to either of the outputs.

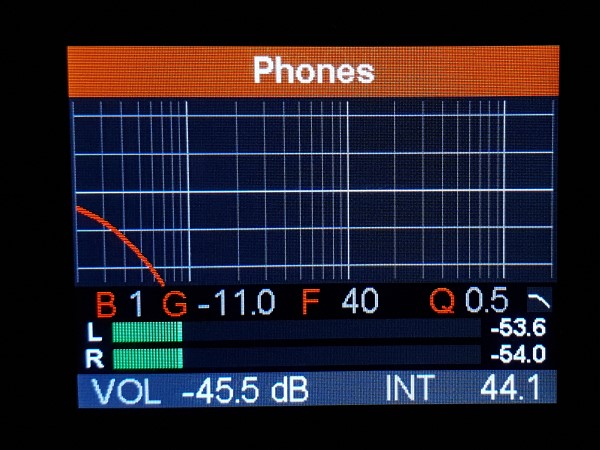

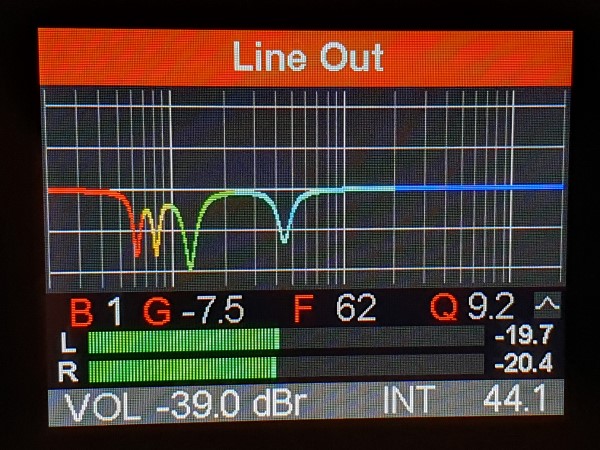

The main advantages of the ADI-2 (in addition to outstanding electrical specs) are flexible settings, versatility and signal analysis capabilities. Let’s start with the analysis. On the front panel of the device, there’s a small display with a usually green spectrum analyser. The colour is customizable. There are also levels of the left and right (or right and left, whichever you set) channels under it. And at the bottom you’ll see the amplification level and frequency (also customizable). At the top — the name of the output in use.

The hardware spectrum analyzer helps tech savvy audiophiles unravel the main mystery: is it the headphones mumbling/screeching/just messing it all in the middle of the range, or is it just what’s recorded in the track? The spectrum analyzer answers this question momentarily and in a very unambiguous and uncompromising way, showing levels at frequencies from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. Within just a few seconds you’ll know, for example, that in the very beginning of the Lamb’s ‘We Fall In Love’ there’s really a dominating sub-bass, the Lynyrd Skynyrd’s ‘Sweet Home Alabama’ is rich not only in middle-range spectrum, but also contains quite a lot below 60 Hz and above 15 kHz, and those farts and croaks in the El Huervo’s ‘Daisuke’ starting from 0:57 are not because of poor recording quality or some screwup, but it’s the way the artist wanted it to sound. And, conversely, Jack White’s Why Walk a Dog? has been originally recorded with clipping (as actually is every other track on the Boarding House Reach album). So, as soon as you start to have a feeling that something’s wrong, you just check the spectrum analyzer and the levels, and they show everything without a fail.

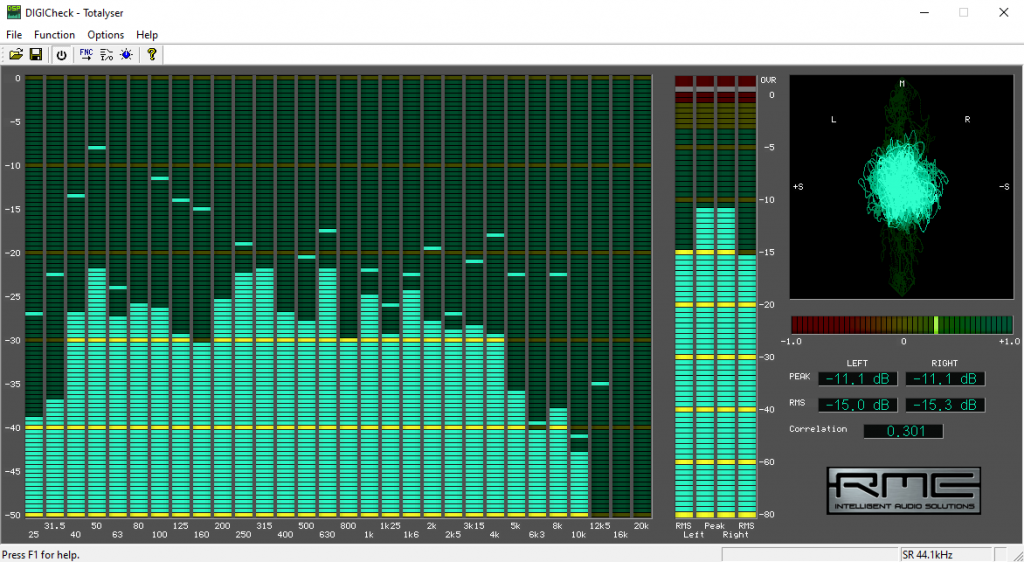

The second way to analyze the sound is to use the DIGICheck software. It’s only compatible with RME’s DACs and, as far as I understand it, analyzes the data from the ADI-2 circuits. DIGICheck shows a certain number of screens with different data, but the most important one is ‘Totalyser’:

At the left, you can see the same spectrum analyzer, just in a more detailed mode. Then you see the levels and a goniometer, no kidding. Basically, a goniometer is a tool to measure angles, But in this context, goniometers usually show Lissajous curves (so, a goniometer is an oscilloscope), allowing assessment of the stereo channels separation degree. In other words, if the music is recorded in mono, the chart will show a vertical line. And if in stereo — some wide scribbles. There’s also an interesting parameter down below — ‘Correlation’. It’s a correlation coefficient (integral of the product of two signals from the left and the right channels over time, normalized over a time period). The closer it is to 1 — the closer the sound is to mono, and the closer it is to zero on the right — the ‘wider’ it sounds, if negative — then the channel phases are inverted.

If I must skip going deep into theory, the goniometer’s (and correlometer’s) measurements can be used to objectively evaluate how much ‘stereo’ a particular track should sound. Yet again, you’ll immediately discover that the Heliocentrics’ ‘Oh Brother’ (as well as all other tracks on the same album) is virtually mixed in mono, and the ‘These Stones Will Shout’ by Raconteurs should sound clearly separately — via the left and right channels, and the correlation coefficient is somewhere in the range from -2 to 0.7 for the most part of the track.

That is, at the very moment a tech savvy audiophile starts to think something’s wrong, the ADI-2 rushes to rescue and shows the exact measurements to dispel all doubts of the restless mind. In figures we trust.

The equalizer is parametric (5 points) and hardware-based. You can configure up to 20 presets for each input, and these will be automatically applied, when you power on the device (or when you route the sound source through it). For the 3 middle points a bell filter is used, for the first and the fifth — either a bell, or low/high pass, or low/high shelf. Of course, each point requires a frequency, an up/down correction value and a Q factor specified. Not only does the equalizer allow you, of course, to equalize the sound, but also to ‘cut off’ the entire rest of the frequency spectrum at the expense of the first and the fifth points and enable only higher or lower frequencies for listening.

There’s also a ‘Loudness’ setting in here, which is a dynamic loudness compensation. This one allows compensation of loudness of lower and higher frequencies in accordance with the Fletcher-Munson curves (see above). Moreover, you can separately set the gain for higher and lower frequencies as well as the very end of the lower frequency curve, the beginning of the higher frequency curve and a minimum volume of sound.

Or, if you don’t want to fine-tune these, just use the ‘Bass gain’ and ‘Treble gain’ settings to set up your preferred frequencies. Let’s say, it’s a static loudness compensation tool.

Interestingly, the equalizer and loudness compensation settings (both dynamic and static) can be applied at the same time.

In essence, you can easily configure the headphones’ sound to your liking or eliminate any resonance your room may create so that the speakers don’t mumble.

Apart from everything said above, you can also configure:

- soundstage width adjustment, from stereo (1.00) to mono (0.00) in 0.01 increments;

- mid-side processing (decoding), which, if applied to stereo tracks, allows you to listen the mono and the stereo components of the track separately via left and right earcups;

- crossfeed (mixing in stereo channels) of 5 different types;

- changing the channels polarity;

- choosing one of 6 digital filters, including NOS (for those with particular tastes in sound).

And there are piles of other settings, including the UI colour scheme. And also one particular trick: dedicated sample audio files analysis and a ‘Bit Test Passed’ message when no distortion is detected.

In other words, this is a way to make sure that the data reaches the DAC unchanged, nothing related to the sound is changed by any drivers or software, and the hardware is running in bit-perfect mode. A curious fact, the tests are passed only if you choose the ASIO driver of the device as output interface in the desktop media player. When in DirectSound or WASAPI modes, the OS somehow changes the sound. By the way, the ADI-2 DAC driver can mix the ASIO output with other sound streams in the system.

And now, let’s get to the main point – the sound, as they like to put in those ridiculously pompous dedicated articles. The ADI-2 DAC sound is a benchmark for audio. You hear the music exactly as it was recorded. There is not much to add.

The ADI-2 DAC is basically a marvel in the world of engineering, a perfect benchmark sound source that allows you to listen to music at the highest technological level and to customize the sound down to the tiniest element. It doesn’t require any burn-in, doesn’t take too much space, and doesn’t require any magical supplements (e.g., a wooden stand made of some precious timber fibers).

For me, the combination of the ME and the ADI-2 DAC became a true cure for this compulsive desire of ‘the special sound’, which I described at the beginning of this post. It’s just that: for three months now I just tune the equalizer once in a while and for the first time in a long while — I listen to the music, not the equipment.

P.S. So, maybe it’s all about the hardware equalizer, not the headphones?

Any headphones have certain restrictions imposed by the drivers’ properties, material properties of the drivers, etc. Sometimes, when tuning the sound using equalizer, the headphones’ properties change in a non-linear way. For example, with the waterfall change, additional resonance appears. That is, some headphones can be equalized easily, and some just cannot. For example, the ME can be configured within a very wide range.

P.P.S. I’ve just happened to check the Meze Empyrean and the ADI-2 DAC prices… So, is there a way how to enjoy music at a somehow lower price?

The evaluation of musical content is not only a matter of equipment, but also a few other additional factors, which were described above. The main factor is the ears (i.e. the brain) of a specific listener. That being said, the answer is simple: just go and listen for yourself. And if you can’t tell the difference in sounding of Meze Empyrean and, for example, HiFiMAN Arya, – go for it, it’s your perfect opportunity to save money. As for DACs with equalizing capabilities, unfortunately, I don’t know any direct substitutes for the ADI-2 DAC. P.P.P.S. In the table below you’ll find the settings for the ADI-2 DAC equalizer, if you want to get absolutely neutral sound (IEF Neutral) when listening your Meze Empyrean, based on the measurements taken from crinacle.com:

| Band | Type | Gain | Freq | Q |

| 1 | Shelf | -5 | 260 | 0,8 |

| 2 | — | -3 | 1,12 | 0,5 |

| 3 | — | 5 | 1,68 | 0,8 |

| 4 | — | 7 | 8 | 1,5 |

| 5 | Peak | -8.0 | 15 | 1,5 |

Like this post? You can support me on patreon.